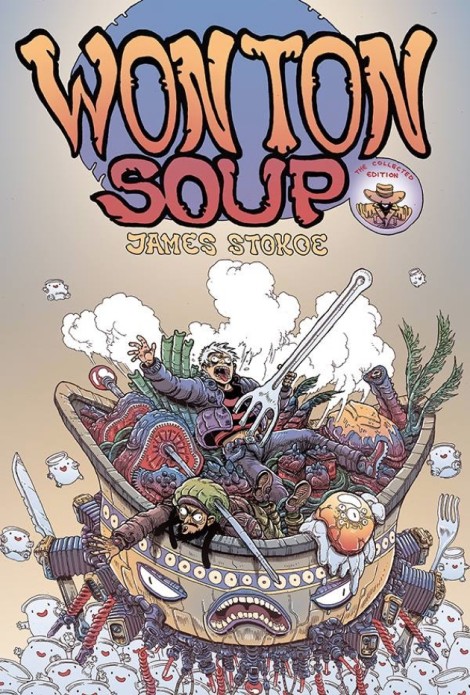

Written and Drawn by James Stokoe

Published by Oni Press

I have this aunt who used to invite me over for dinner and a movie on Friday nights my last year of high school. I’m sure it seems pretty fucking nerdy to be a high school senior who favors movie nights with a relative, but most of you haven’t had my aunt’s cooking or seen her film collection. Those interests collided in an especially noteworthy way one evening when she introduced me to Tampopo, an odd anecdotal film about Japan’s obsession with food and one trucker’s search for the greatest ramen house in the country in particular. It’s been a while since I’ve revisited the film, but Oni Press’ new collected edition of James Stokoe’s Wonton Soup has it on my mind again, and not just because they both have an appetizing devotion to Asian noodle soups.

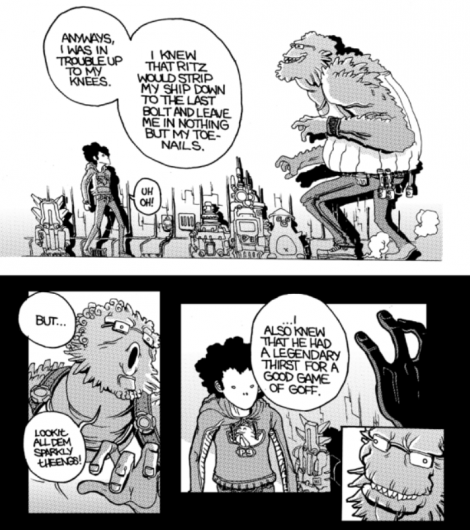

An intriguing blend of Tampopo’s roving gastrological focus and the urban space cowboy grit of Dark Star (another favorite of that aunt’s), Wonton Soup isn’t your normal kind of sci-fi comic. For starters, the protagonist is Johnny Boyo, a genius chef in training who abandoned culinary academia in favor of travelling the galaxy as a space trucker. Like Tampopo’s own grizzled trucker ramen connoisseur Goro (whose name is echoed by Boyo’s), he does this not out of any trucker calling but in order to have more opportunities to find the universe’s best dishes, wherever they might be. Stokoe doesn’t rag on space trucker life, but he doesn’t glorify it, either—there’s adventure to be had and Boyo’s trucking partner is a particularly charming yet filthy galactic lothario, but there are also space ninjas and explosive cargo (conveniently called S.H.I.T.T.) and pirates who can only be swayed if you’re a decent enough player of what goes for Chess out on the Milky Way.

If you’ve seen Stokoe’s art before, you know how singular his style is—backgrounds that look like vivid graffiti doodles, characters that are chic without trying, heavy detail leading into moments of quietly epic expanses of white space and blocks of black that sneak out from cutaway panels rather than frame them. There’s a bit of Brandon Graham in there, which is no coincidence given that Graham is a former neighbor of Stokoe’s and pens the intro to this collection, but mostly in the sense that they appear to share certain influences. Stokoe’s storytelling is more intimate and deliberate than Graham’s, honing in on internal characterization and intense examinations of processes. King City is undoubtedly a sister work to Wonton Soup (Stokoe, after all, contributed a story to it, too), but in that work Graham is an artist who crams every millimeter of panel space with clever detail, while Stokoe is the kind of guy who emphasizes his eye for design through stark blank backgrounds. Which is perfect for a story about space, that ultimate example of expansive unknown.

That said, Stokoe’s art is at its most expressive when grounded. In the first half of the collection, that’s highlighted by a chapter where Boyo and his partner Deacon are forced to get ship repairs on a planet that is conveniently home to both the elite culinary school he dropped out of and Citrus Watts, the long distance girlfriend he’s somewhat avoiding. Boyo is avoiding both not because he doesn’t love them, but because space was calling and he couldn’t say no to all the potential riches it offered. Citrus is a world class chef of her own, and one of the best sequences in the chapter has Stokoe pausing the action to showcase her cooking abilities, zooming in on each element of the process as Boyo offers commentary and explains what a treat it is to see another master chef work.

It’s here where things get kind of meta. As Graham points out in the introduction, Stokoe works at his own pace and releases comics when he wants to rather than out of any kind of obligation. Hence his upcoming Avengers work being a one-shot set in a future timeline. Throughout Wonton Soup, Boyo asserts that he went into space trucking because he loves food and cooking and the job offered the opportunity to enjoy this things more or less without interference. No grades, no endless explorations of menus, no traditions to follow beyond reason. That may as well be Stokoe’s modus operandi, too, since he’s a creator who follows his passions rather than a paycheck or, as Graham puts in the introduction, he’s an artist who “could be sent to the moon and as long as his crater had enough paper in it and a nearby Daedalus Sandwich Shop he’d be set.” So it isn’t too surprising that Wonton Soup is at its most vivid and expressive when Stokoe is detailing the art of cooking and eating food, whether it’s in a MacGyver-like approach to improvising a meal with limited resources or a culinary battle where the judge is a massive interstellar tongue. In Tampopo, the meta elements came in to play via a food and film obsessed Yakuza, who dressed like a future Warren Ellis character with his white suits and trim cut, and commented on the film and the culture it represented while also taking detours to berate an audience member for eating too loudly in the theatre or offering up tips for how to make the best yam sausages with his last dying breaths. Boyo’s inner monologue in the first half of Wonton Soup fulfills a similar purpose, indirectly commenting on the story while providing cooking advice and observations about people’s experiences with food and its preparation.

In the second half of the collection, the meta elements get a bit more direct, as a drug trip using the brains of the elder from a race of near extinct dinosaur-like merchants causes Boyo and Deacon to become literally lost between the panels, culminating in a sequence where Stokoe tells the reader that he wasn’t able to finish up the panels because his mind’s eye was now tripping along with the duo but they could complete it themselves by cutting out some drugs and ingesting them. The aftermath has the twosome commenting on Deacon’s own underdeveloped state, necessitating a flashback where Deacon even demands a title page. It’s another example of Stokoe’s inherent playfulness and passion for the process of the medium—rather than intellectually break down tropes and traditions, Stokoe just has fun with them, celebrating the comfort they bring while taking pleasure in providing his own spin on them. Here the food element moves to the back and the drug and sex elements take its place. There’s the aforementioned trip, but there’s also Deacon’s origin’s connection to the black market trade of milk taken from a “sex bear.” It’s gonzo and goofy but Stokoe takes it as seriously as the culinary aspect, and provides just as much fictional insight and detailing of the process. And oh what a process sex milk acquisition is.

Stokoe’s career path may seem a little unorthodox, but like Deacon and his sex bear, his work is defined by a near insane devotion to extracting raw passion as well as Boyo’s shared devotion to the art of the process. If it’s even half as taxing as sex milking, it’s not hard to see why Stokoe moves at a deliberate pace, releasing work only when every ounce of raw potential has been gleamed. Stokoe had mostly released one-shots and made occasional appearances in anthologies when Wonton Soup was originally released, so reading it now, after Orc Stain, after Godzilla: The Half-Century War, after the announcement of his Avengers 100 gig, it’s kind of incredible to see how he has remained basically faithful to the ethos he outlined for himself in Wonton Soup even as the gigs have become increasingly higher in profile, and how his style has remained consistently confident and assured and playful throughout. Like Goro and Boyo know all too well, haters won’t understand a devotion to craft that borders on the extreme, but it’s not hard to understand the excellence of the end results.

Wonton Soup: Big Bowl Edition comes out tomorrow through Oni Press. Order a copy now.

Nick Hanover got his degree from Disneyland, but he’s the last of the secret agents and he’s your man. Which is to say you can find his particular style of espionage here at Loser City as well as Ovrld, where he contributes music reviews and writes a column on undiscovered Austin bands. You can also flip through his archives at Comics Bulletin, which he is formerly the Co-Managing Editor of, and Spectrum Culture, where he contributed literally hundreds of pieces for a few years. Or if you feel particularly adventurous, you can always witness his odd .gif battles with Dylan Garsee on twitter: @Nick_Hanover

Leave a Reply