For one week in 2012, Facebook blatantly manipulated the posts nearly 700,000 users saw on their feed in order to gauge the impact the social media platform had on human emotion, removing positive or negative posts to make some people have “happier” feeds while others wound up with “sadder” ones. When news of this experiment broke two years after the fact, there was an outcry as consumer fears over “subliminal” messaging became more real than any stories about theatre lobby sales ever were. It felt like a betrayal, a manifestation of every paranoid thought about social media’s control over our lives and well-being. And it was made worse by the official Facebook response, a statement that not only was it merely meant to help them improve their services but that it turned out to be a kind of worthless experiment anyway. To quote Facebook employee and study author Adam D.I. Kramer, ” In hindsight, the research benefits of the paper may not have justified all of this anxiety.” There was already data that suggested regular interactions with our friends on Facebook can make us feel sad and lonely but to discover the company was helping that process along and that it didn’t yield them the results they wanted? That’s like something from a dystopic work. Specifically, it’s a lot like the future Ryan K. Lindsay and Owen Gieni imagine for us in Negative Space.

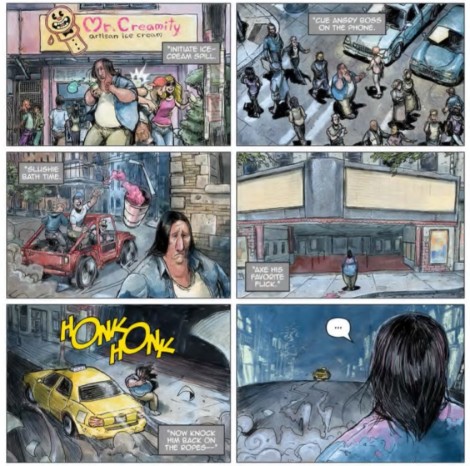

Subbing in raw emotion for Cabin in the Woods’ virgin sacrifice angle, Negative Space is a narrative in fractures, the story following the Kindred Corporation’s surveillance of Guy Harris, a writer with acute emotional empathy who gets writer’s block while crafting his suicide note and takes a little walk for inspiration. Kindred is on Guy’s trail because he’s an empath, “the sort of emotional conduit you used to only see in saints,” as Guy’s main monitor Rick so eloquently puts it. Like Facebook, Kindred isn’t content to let Guy inspire himself out of suicide so they’re taking action, turning a bad day even worse with the timely intervention of ice cream spills, angry employer calls and a little apartment bombing. Negative Space splits its time between Guy and his torturers, giving insight into the bad things that are happening to him before they happen and feeding into the feeling everyone has had on their worst days: why the fuck is this happening to me? is the universe mad at me? what did I do wrong?

In Guy’s case, his crime is caring, giving too much of a shit about a world where helping others out doesn’t necessarily get you any further in life, arguably it puts you behind most of the time. This being a creepy story, there’s clearly more to it than that and eventually the reader gets a peek behind the curtain, as mentions of otherworldly monstrosities that feed on emotion come up and Kindred’s existence suddenly seems a little less capitalistic and a little more anti-apocalyptic. That’s honestly a little disappointing because Negative Space’s best moments come when Gieni is allowed to embrace his inner Bill Plympton, putting Guy through an absurd physical and emotional gauntlet, twisting cartoon tropes like explosions and spilled liquid gags into truly sad shit, getting impressive mileage out of slack body language and darkly comedic framing as close-ups on teary eyes and downward frowns. The Big Picture conspiracy is mostly kept for the end but Gieni expresses character emotion so well it could sustain an entire book of bad days rather than merely a single introductory issue.

Gieni’s character design is built on extreme features, which amplifies the absurdity but also allows for clearer emotion, but his backgrounds and textures take a softer approach, like a watercolor Richard Corben. The light colors mix well with the elongated expressions but they also bring a lot of life to the city Guy inhabits, making it seem effortlessly timeless, combining modern elements like Kindred’s tower headquarters with cobblestone streets, barnacle-encrusted docks and rows and rows of brick townhouses. In an era of digital coloring and Photoshop layouts, Negative Space stands out as lovingly handcrafted, something that thematically connects with a story about human connection and interconnectedness.

Lindsay’s work on other series like Headspace was sometimes a little too high concept and there is a bit of danger of that here with Negative Space’s Lovecraftian elements, but Gieni’s style is so refreshing and singular it has the potential to make up for any number of future narrative hiccups as long as Lindsay allows Gieni to continue to showcase his knack for communicating real human emotion on the printed page. The story has also already set itself apart from Cabin in the Woods in this respect by making Guy a believable, human character rather than a trope and that’s more than can be said for a large percentage of pop comics, as well. Gieni and Guy might not be impacting as many emotions as Facebook just yet but Negative Space is well on its way to proving itself as a far more emotional and profound high concept work than the bulk of its competitors, making it a more than worthwhile break from the sad and lonely pits of your Facebook feed.

Negative Space #1 comes out this Wednesday, July 8th, through Dark Horse Comics.

Nick Hanover got his degree from Disneyland, but he’s the last of the secret agents and he’s your man. Which is to say you can find his particular style of espionage here at Loser City as well as Ovrld, where he contributes music reviews and writes a column on undiscovered Austin bands. You can also flip through his archives at Comics Bulletin, which he is formerly the Co-Managing Editor of, and Spectrum Culture, where he contributed literally hundreds of pieces for a few years. Or if you feel particularly adventurous, you can always witness his odd .gif battles with friends and enemies on twitter: @Nick_Hanover

Leave a Reply